What A Trip To The Seaside Tells Us About Britain’s Political Shift

Cameron Iveson

Public Affairs Lead

9 October 2025

As I arrived at the Premier Inn facing the Bournemouth Pavilion for the second time in two weeks, the polite gentleman at reception asked me “are you here for the Conference? … There was one last week, it seems like all the lefties are coming to Bournemouth.”

Whether Lib Dems can be described as a left-wing party is a conversation for another time. But this interaction draws on something much more important – Britain now has a five-party system, and the public is more alive to the other parties’ programmes than it likely ever has been throughout British history.

The Two-Party System is Dead, Long Live The Five Party System

A big claim but consider the polling. The two-party system has been in decline since the 1950s, with the two main parties taking almost 97% of the vote in 1951. By 2024, that figure sat at just 57%. In the September YouGov MRP poll, the Greens and Liberal Democrats were polling at 11% and 15%, respectively. As widely reported, Reform UK is polling at 27%, with the two dominant parties of the last century, Labour and the Conservatives, sitting at a lowly 21% and 17%.

Why is this important I hear you ask. On the horizon, we potentially have ground shifting local elections, with the public divided over key issues from immigration to the economy. YouGov polling last week also found that 46% of the public preferred having a greater number of smaller parties in British politics, compared to only 23% who would rather have two larger parties. Get ready for significant change across London and the UK — shifts that could reshape attitudes towards development and investment decisions.

My colleague Nick Bowes attended Reform UK’s conference in Birmingham and off I went to Bournemouth to see the Liberal Democrats and the Green Party. Here’s what I learned.

What was the vibe like?

An optimistic, invigorated atmosphere spread across both conferences. Both parties have boosted their number of MPs and councillors putting attendees in a cheerful mood. Business presence at both was limited, with the conferences instead being dominated by passionate delegates.

Lib Dems: One of the key discussions across Lib Dem members was whether Leader Ed Davey MP’s stunts risked undermining his party’s credibility. This year, we had the conference guide adorned with Davey on a jet ski and MPs playing cricket on the beach. Does it impact their credibility, or does it improve their likeability? Who am I to judge other than to point out Davey (and his antics) took them from 11 MPs in 2019 to 72 MPs in 2024.

What all Lib Dem delegates wanted to speak about was the rise of Reform UK. A policy-light conference across the main hall and fringe instead chose to continue focus on the Blue Wall strategy – a plan to appeal to the swathes of disillusioned Conservative voters in southern England who are unlikely to back Reform UK. Davey’s headline speech led with the line, “Don’t let Trump’s America become Farage’s Britain”, notably opting not to mention Prime Minister Keir Starmer once.

Green Party: There were no obvious fissures in the Green Party, buoyed by its recent election of new Leader, Zack Polanski AM, and Deputy Leaders Cllr Mothin Ali and Cllr Rachel Millward. Despite announcing that the Green Party has more members than the Lib Dems, the same conference space felt like it had fewer attendees.

Anecdotally, the members I spoke to had recently joined from other parties, mainly the Labour Party, referencing Polanski’s commitment to “Bold Politics”. His headline speech appealed to the left wing of the Labour Party while taking aim at Reform UK, with standing ovations for attacks on Trump and his support for Palestine. References to austerity, capitalism and a wealth tax made it feel like a Corbyn-era Labour revival.

Was the built environment discussed?

Beyond the conference mood, both parties’ approaches revealed deeper insights into their policy instincts. The Lib Dems and the Greens identify the housing and infrastructure crises gripping the UK, but both have Not In My Back Yard (NIMBY) campaigners in their ranks. Their approaches at conference reflected their different audiences.

Lib Dems: Housing wasn’t central to the conference and fringe agendas. One could see this as a ming vase strategy – a cautious plan choosing to remain light on detail to avoid losing support. I believe this to be the case as the Blue Wall strategy is in predominantly leafy rural southern areas, more inclined to be against development in their area.

The significant housing moment in the main hall was the passing of a motion on leasehold reform to end, in their words, “the great property rip off for leaseholders”, brought by members and supported by the party’s London spokesperson, Luke Taylor MP. Again, this falls into the cautious category of not dissuading rural voters while backing an existing campaign addressing housing concerns of predominantly metropolitan voters.

Green Party: The opposite of a ming vase strategy, housing was used to demonstrate the leadership’s populist left-wing credentials. Polanski referenced “renters living in shoddy accommodation” who “can’t take another rent hike” and homelessness in his Leader’s Speech. Deputy Leader Millward followed this up a day later referencing a “planning system that prioritises profit over people” and “luxury housing estates that will do nothing to solve the housing crisis,” but her speech was short on how they’d solve any of this.

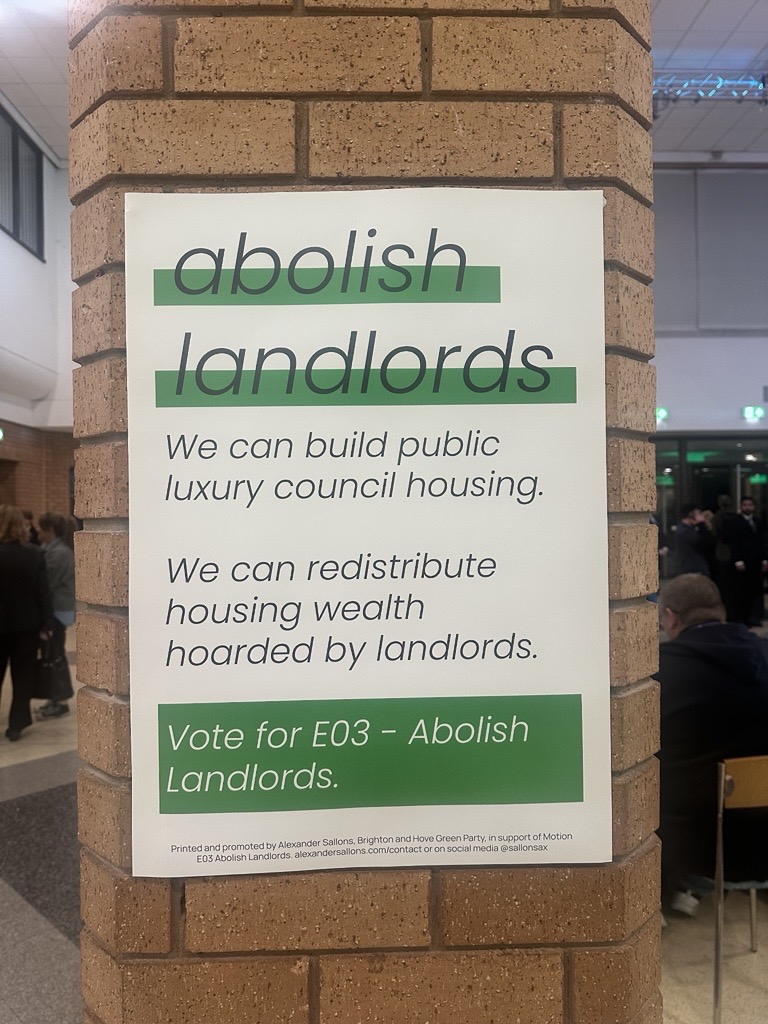

This approach equally apparent elsewhere. I heard the Planning and Infrastructure Bill referred to as the “biggest threat to nature” and on the conference floor a motion was passed to “abolish landlords.” The latter also included rent controls, scrapping Right to Buy, and increasing taxation on and restricting finance for landlords. It’s a populist pitch to rural NIMBYs and young people trying to get on the housing ladder (but I’m unsure whether those in rural areas with a second home will be totally on board!)

What’s next?

With a renewed sense of optimism and the local elections offering a big opportunity to restate their presence on the political scene, the central question is: what’s next?

Lib Dems: There’s a split in the ranks over how the party should seek to grow. Should the Lib Dems continue to build gradually on the Blue Wall strategy, positioning themselves as kingmakers at the next general election — or go big, competing nationwide on a broader platform and challenging Labour in metropolitan areas?

The esteemed Professor John Curtice told a fringe event at the conference that Davey’s cautious strategy is underperforming, arguing it’s failing to attract disgruntled Labour voters. Nevertheless, Davey has set his sights on gradual growth through the Blue Wall approach. The benefit of this strategy is stabilising the Lib Dems as a consistent political force — and I believe he is banking on the continued rightward drift of the Conservative Party, which would only make his own party more attractive to disillusioned centre-right voters.

Green Party: Contrastingly, the Greens are not at a crossroads. At one panel, a Green Council Group Leader was asked whether the party simply needs to do more of the same to defeat Reform UK — their answer was, essentially, yes, but with better communications. This reflects the party’s unified support for its new leader and a strong belief that its populist message can resonate more widely.

Interestingly, the Greens’ Deputy Mayoral candidate for Hackney, Dylan Law, reiterated a big push on local representation rather than national politicking at event in the main hall. Expect a focus at the local elections on doorstep issues and building candidates’ personal votes — anything from bin collections to positions on local developments.

What does it mean?

For business, the political shift isn’t just Westminster theatre — it has real consequences for planning, development, and investment. As smaller parties gain ground, local politics will matter more than ever, with councils increasingly shaped by Lib Dem, Green, and Reform UK representation.

Expect greater local scrutiny of development proposals, sharper divides on environmental policy, and more emphasis on visible community benefits. In short, the new five-party era means navigating a more complex, locally driven political landscape — one where understanding nuance could make all the difference to getting projects over the line.